cw: colonialism, war

I have a habit of following collateral branches of my family tree as far as I can take them and I enjoy learning about the lives of distant relations and the history of the times they lived in as much as direct ancestors!

My 2nd cousin 5x removed Selina Ming (1876–1932) married William Leonard Bibby (1865 – 1937), who is notable for his service with the Oxfordshire Light Infantry around the turn of the 20th century. He served in the colonies and in conflicts across the British Empire during his 17 year army career.

Credit: National Army Museum.

The 43rd Monmouthshire Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry) and the 52nd (Oxfordshire Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry), became the 1st and 2nd Battalions in 1881. William enlisted in the 1st Battalion Oxfordshire Light Infantry in 1885, when he was just 19 years old, and was promoted through the ranks to Sergeant, in 1891. He served in the regiment for almost 17 years, and was deployed in Burma (now Myanmar) and South Africa.

Early life of William Leonard Bibby

William was born in Bethnal Green, London, in 1865, and was the son of a London Police Constable, and owner of a brilliant name, William Risby Bibby (1834–1908) and his wife Frances ‘Fanny’ Prickett (1835–1911). Amusingly, William Risby Bibby’s Metropolitan Police pension record notes that his hair is ‘turning grey.’ He was 55 at the time of his retirement and had been in the Police force for 18 years.

Back to William Leonard Bibby, by when the 1881 census was enumerated, he was 15-years-old and was employed as a Grocers errand boy. His teenage siblings were also employed in typically working class occupations such as barmaid and shopman. After his grocers job, William briefly worked as a clerk for the General Post Office in London. When he enlisted in the army, he was described as 19 years and 10 months old, 5 foot 4 3/4 inches tall and pale skinned with grey eyes and light brown hair.

At the beginning of his army service, William was stationed at home, and achieved a 2nd class certificate of education. He was then posted with his regiment to British India, in preparation for service in Burma.

Burma

In the 1820s, Burmese expansion into Manipur and Assam had created a long border between British held India and the Burmese Empire. The First Anglo-Burmese (1824-1826) war broke out in 1824 over the control of Northeast India and ended in a British victory. Burma lost territory in Assam, Manipur, and Arakan and was weakened both in terms of territory and financially. After the First Anglo-Burmese war, the Treaty of Yandabu was signed between the Burmese Empire and the British East India Company in 1826. Relations were largely peaceful for another 25 years.

From 1851, English merchants in Burma complained to the British in Calcutta, India, about their treatment by Burmese officials at Rangoon and this was used as a pretext for another conflict. The Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852) led to the annexation of Pegu (Lower Burma) by the British and humiliation for the Burmese people.

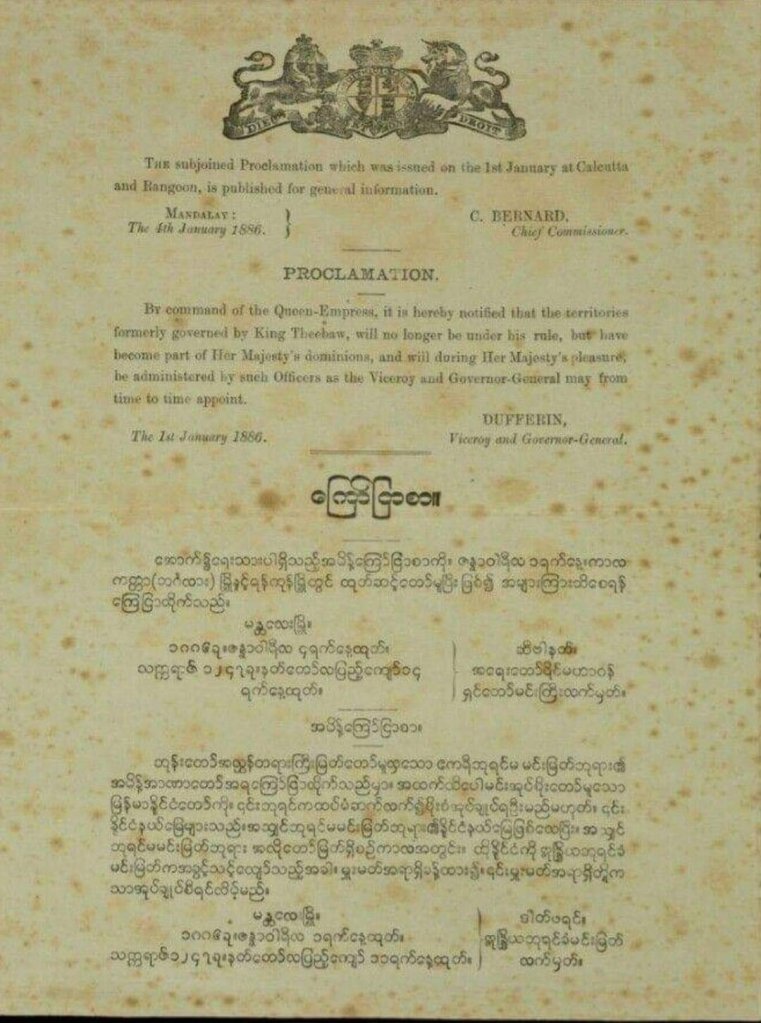

Credit: Wikimedia.

In 1885, the year that William joined the army, the Third Anglo-Burmese War broke out between the British and Burmese Empires, leading to the British annexation of Myanmar (Upper Burma), total British control of the country and a loss of Burmese sovereignty the following year. Burma came under the rule of the British Raj as a province of India, which sparked widespread anti-colonial resistance and resentment by the Burmese people. The British Empire poured military reinforcements into the country, including William who was sent with his regiment to Burma in October 1889 and remained in service there until 1893. Despite the resistance, British rule in Burma lasted until 1948. After a national independence movement in the early 20th century it became a fully independent republic as the Union of Burma.

Credit: British Empire and Commonwealth Collection at the Bristol Archives.

After the years posted in Burma, the Oxfordshire Light Infantry were stationed at home for the next 7 years. In 1896, William married my collateral relation Selina Ming (1876–1932) at the brides local parish church in her hometown of Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire. About a year into the marriage, Selina gave birth to a son, William George Leonard Bibby (1897-1970) on the 16 August 1897. The Oxfordshire Light Infantry were next sent to South Africa and while William was stationed overseas from 1900 to 1902, Selina lived with her parents and young son. She is inaccurately recorded with her maiden name in the 1901 census.

Credit: FindMyPast.

South Africa

William served in South Africa during the second conflict between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Transvaal and the Orange Free State), over the Empire’s influence in Southern Africa. The Boer’s were Afrikaans-speaking white South Africans descended from the Dutch East India Company’s original settlers who had lived at the Cape of Good Hope. Between 1652 and 1795 the Dutch controlled the Cape Colony, which was strategically important to naval powers in relation to Indian and Far Eastern maritime traffic.

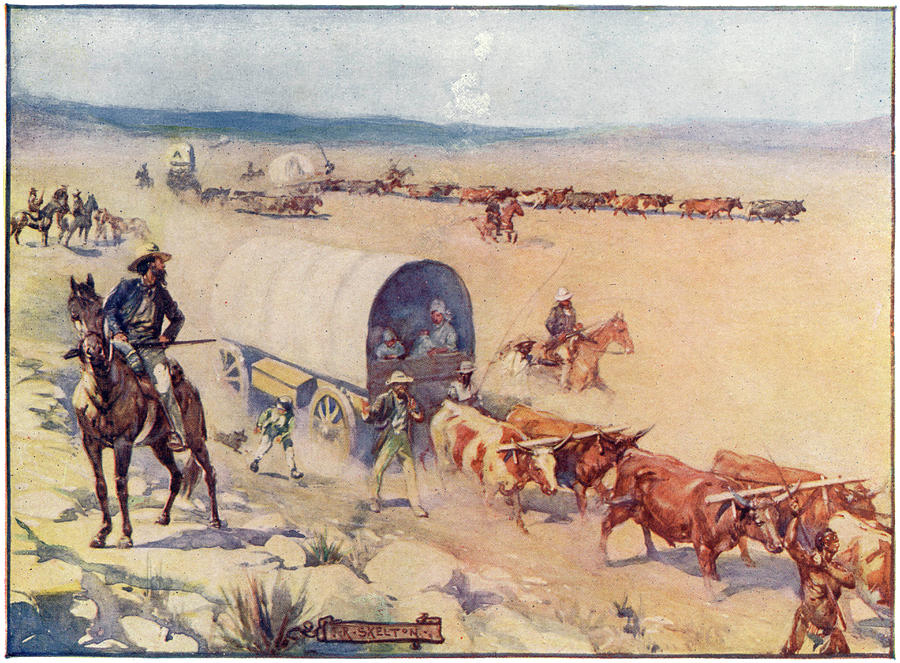

Credit: Mary Ann Evans Picture Library.

The Cape Colony was incorporated into the British Empire in the early 1800s, during the Napoleonic wars in Europe. During the first decades of the 19th Century, resentment in the Cape Colony grew amongst the established Boer communities towards British rule. Many were unhappy that English replaced Dutch as the official language of the colony, they experienced political marginalisation on the eastern Cape frontier, and they generally disagreed with the British policies, including the abolishment of slavery. This lead to the ‘Great Trek’ from 1835 to the early 1840s, where approximately 15,000 Dutch descendants left the now British Cape Colony and travelled across the Orange River into the interior of South Africa to establish independent republics. In a letter to the British Colonial Administration, written in 1837, the Boer leader Piet Retief stated that: ‘we quit this colony under the full assurance that the English Government has nothing more to require of us, and will allow us to govern ourselves without its interference in future’. The Boers who took part in the Great Trek identified themselves as ‘voortrekkers’ and were about a fifth of the Cape colony’s Dutch-speaking white population at the time.

Credit: Wikipedia.

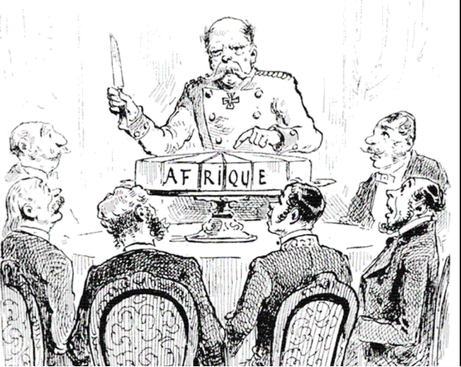

After the discovery of diamonds in 1867 near the Orange and Vaal Rivers in voortrekker controlled territory, a diamond rush was triggered and the British Colonial Secretary, Lord Carnarvon, proposed a confederation of South African states, which was rejected by other colonial power. The so called ‘Scramble for Africa,’ ‘Partition of Africa’ or ‘Conquest of Africa’ between several European powers was well underway by this time, during an era now known as ‘New Imperialism’. There was a race for colonial expansion as the various powers tried to gain territory and secure their access to natural resources in order to exploit and steal them for profit. Many conflicts were fought on the African continent and African languages, borders, cultures and political systems that existed before colonisation were swept aside by European nations in the process of colonisation. Thousands of indigenous African people were killed, either by violence or as a result of diseases brought by European colonialists.

In the 1870s, the British annexed West Griqualand (where the diamond discoveries had been made), in 1877 they attempted to annex the Transvaal and in 1879 they defeated the Zulu Kingdom at the Battle of Ulundi. Not long after these events, the First Anglo-Boer War erupted in 1880 between the British and the voortrekkers, with a victory for the Boers after just three months of armed conflict. Before the Anglo-Boer Wars, the British Army were accustomed to fighting against enemies inferior in their armaments, organisation and discipline, but even though the Boers were outnumbered by the British, they were excellent marksmen, competent horse riders and had years of experience fighting frontier skirmishes with indigenous African tribes. The British underestimated their opponents and had a casualty rate of 46%, whilst the Boers only had a single mortality and six men wounded. The British Empire had not lost a war to a rebellion since the American War of Independence in 1783, so being defeated by the Boers was an embarrassing disaster for the British government so soon after the victory against the Zulu nation.

Credit: National Army Museum.

At the Berlin Conference in 1884, the United States of America, Ottoman Empire and 12 European countries divided up most of the African continent between them, with the hope to avoid wars with each other. This is considered the formalisation of the ‘Scramble for Africa.’ There were no African representatives and their views were not considered.

Credit: BBC.

In 1886, gold was found in the Transvaal and there was an influx of English-speaking people, called Uitlanders (Outlanders) by the Afrikaners, who were attracted by the goldfields. As the population swelled in the area tensions began to rise again between the British settlers and the independent Boer nations and, on 11 October 1899, the second Anglo-Boer War broke out. Sieges started taking place at strategic locations across Transvaal.

The wars have been given many names both at the time of the conflicts and by subsequent generations. To the British they were known as the Boer Wars, whereas for the Boers, they were called the Wars of Independence. The first Boer War has also been proudly named the Transvaal Rebellion by Boer descendants. Many Afrikaaners today refer to the wars as the Anglo-Boer Wars, which is the most accepted and widely used name. Scholars prefer to refer to the overall conflict as The South African War, arguing that all South Africans, both white and black, were affected by the war and using this moniker acknowledges this.

William’s engagement in the South African conflicts

The Oxfordshire Light Infantry sailed for South Africa on 22nd December 1899, two months after the start of the second conflict, and arrived at Cape Town on 13 January 1900. He was part of a British relief effort, particularly needed after the disastrous ‘Black Week’ in mid December 1899 where the British army suffered losses on three fronts with 2,776 British soldiers killed, wounded or captured. Pouring in more soldiers was part of the effort of the British to turn the tide in the conflict and recover from their losses. The defeats were a major shock to the British public and had caused a revaluation of military tactics.

Credit: Antiquarian Auctions website.

The Bucks Herald Newspaper published an obituary after William’s death in 1937, which recounted an action he engaged with alongside his Oxfordshire regiment during the Second Anglo-Boer. The fighting took place in 1900 at Brakfontein Farm, in the Eastern Cape, which held provision stores nearby to where the largest of the Boer encampment at the time was located. Burning or otherwise destroying farms and slaughtering livestock was a tactic of the British scorched earth policy to deprive their enemy of food supplies. The obituary states that:

‘an escort of 12 men, under Sergnt. Bibby, and six Yeomen, were sent out by wagon for the purpose of destroying the roof of Brakfontein Farm. About noon the same day firing was heard in that direction, and 20 Yeoman, 100 Infantry and 2 guns went out and took up position on a ridge above the farm. The enemy were located in a kraal, about 3,000 yards away, and after shelling them from the rocky ridge above the farm, they cleared off and the wagons were bought in. The escort had been attacked soon after leaving the farm on the return journey, and, being surrounded, took cover in the sprint. The Boers kept up continuous fire but only killed one mule and wounded four. When first attacked, one of Yeomanry galloped back to give the alarm to camp, but the horse was killed before he had gone 70 yards.’

Credit: National Army Museum.

The Oxfordshire regiments service also including the relief of the besieged British garrison at Kimberley and fighting at the Battle of Paardeberg in 1900 alongside the Royal Canadian Regiment, who were on their first overseas posting. British victory at Paardeberg resulted in the surrender of the Boer General Cronje, but many Boers pledged to fight the British until the bitter end. For the first six months of 1901, William’s battalion was stationed at the garrison of Heilbron, where the surrounding area was rife with guerrilla activity from Boer fighters, before moving to the Orange River Colony in July. The last of the Boers surrendered in May 1902 and the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging was signed, ending the existence of the Transvaal and Orange Free State as independent Boer republics. After the war, many Boers emigrated abroad, whilst others remained and tried to rebuild. The Union of South Africa was established as a dominion of the British Empire in 1910.

William’s regiment returned home in 1902 once the hostilities ended. The regiment was stationed at Chatham, Kent when they arrived in England and he was the only non-commissioned officer to be mentioned in the Oxford Light Infantry’s official regimental history from the Anglo-Boer War period.

Credit: Uniformology.

A memorial to 142 men from the regiment who died during the Anglo-Boer War was erected in 1903 in St. Clements Church graveyard, Oxford, Oxfordshire. It was unveiled by the Bishop of Oxford on 19 September 1903 despite not being complete, so that members of the first battalion could be present before departing to their next posting to India, where they would remain until the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. 5,000 local people were said to have attended the unveiling to honour the regiment. The monument has since been moved to accommodate building works and now stands at the entrance to the Edward Brooks Barracks in Shippon, where the County Territorials are based in the Territorial Army centre. It shows a soldier in pith helmet and South African campaign uniform, holding his rifle in the ready position, alongside the names of those soldiers killed in the conflict.

Credit: BereniceUK at http://www.angloboerwar.com.

After military service

William left the army in 1903 and was awarded an army gratuity. He was awarded the Indian General Service Medal with 1 clasp (Burma 1889-92), the Queen’s South Africa medal with 4 clasps (Relief of Kimberley, Paardeberg, Drifontein and Transvaal) and the King’s South Africa medal with 2 clasps (South Africa 1901 and South Africa 1902) in commemoration of his service.

Credit: Chester Medals.

William found employment at the Nestle Milk Factory and worked there as a milk packer then foreman for the rest of his working life, before retiring in 1926. He eventually settled in his wife Selina’s birthplace of Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, with her and their son. The couple had 4 more children and nearly 30 years living together before Selina passed away in 1932. William survived her for another 5 years.

William was an active member of the British Legion Club in Aylesbury and was appointed steward from 1927 to 1933. He was described in another obituary, from the Bucks Advertiser and Aylesbury News as a popular figure amongst the local Legion who was affectionately referred to as ‘Old Bill’. He passed away in 1937 and his funeral was attended by many family members and a representative from the British Legion.

Leave a comment