cw: death records, depiction of battle.

When researching Irish family history, it is important to expand your pool of sources, think creatively and have an understanding of naming patterns, changing parish boundaries and even some Latin. Here is an A-Z guide of how to explore your Irish genealogy.

Abbreviations

In addition to abbreviations that you may see in any genealogical research, there are some that are handy to be aware of when conducting Irish research:

APGI: Association of Professional Genealogists in Ireland (http://www.cigo.ie/apgi/).

CIGO: Council of Irish Genealogical Organisations.

C of I: Church of Ireland.

DED: District Electoral Division.

GROI: General Register Office of Ireland.

JAPMDI: Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead in Ireland (see below and www.memsdead.com/overview).

NAI: National Archives of Ireland (https://www.nationalarchives.ie/).

PRAI: Property Registration Authority of Ireland.

Catholic qualification rolls

In 1774 the Penal Laws were relaxed for Irish Roman Catholics who renounced their religion, converted to the protestant Church of Ireland and took the Oath of Allegiance to the King at the Assize courts. The names of these people were recorded in the Catholic qualification rolls, with over 50,000 people listed, often because this was the only way Irish Catholics could gain any civil rights.

The Catholic qualification rolls (1700–1845) can be searched online via the National Archives of Ireland website: https://census.nationalarchives.ie/search/cq/home.jsp

The rolls are also available on Ancestry: https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/62057/

Census Substitutions

After the Four Courts fire of 1922, covered in my post ‘Why is Irish genealogy so challenging’, most Irish census returns before 1901 were destroyed but some fragments survive covering the years 1821 – 1851 for some counties.

The records that survive are for Antrim, 1851; one ward in Belfast city, 1851; Cavan, 1821 and 1841; Cork, 1841; Dublin city (index to heads of household only), 1851; Fermanagh, 1821, 1841 and 1851; Galway, 1821; Offaly, 1821; Derry, 1831 – 1834; Meath, 1821 and Waterford, 1841.

The National Archives of Ireland hold the surviving records which can be searched on: http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/search/

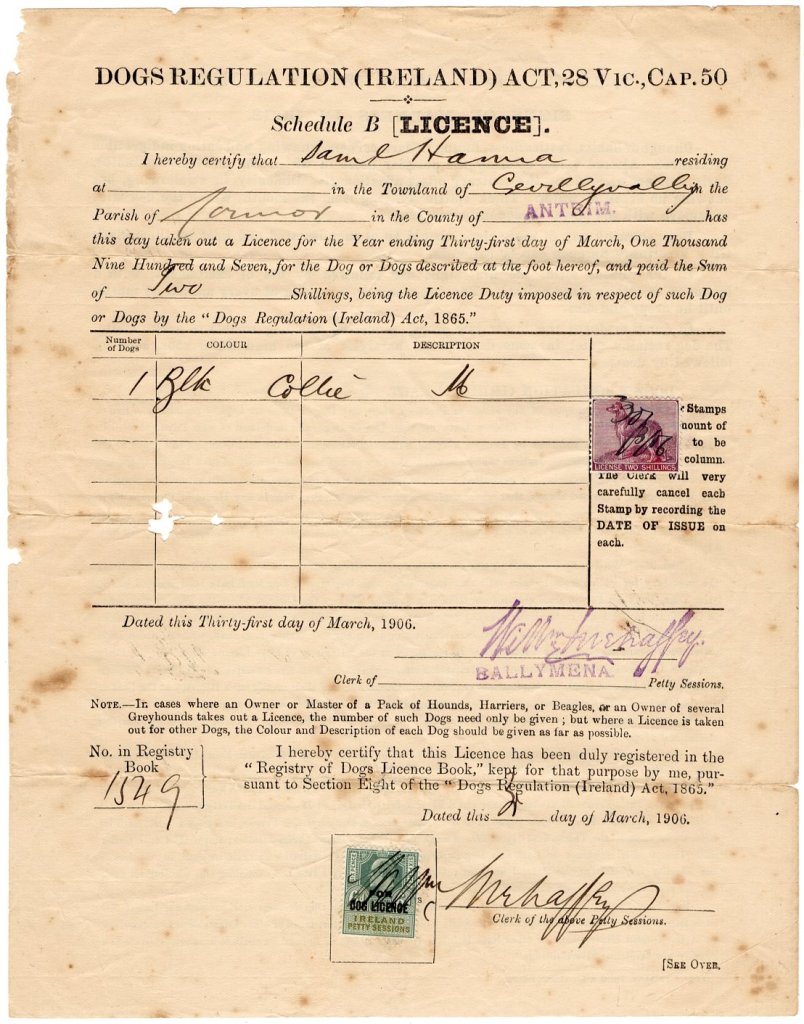

Dog Licenses

In an attempt to reduce the number of stray dogs in Ireland, in 1866 the government introduced Dog Licenses, which are a surprising resource for Irish family history! They record the individuals name, residence and the date on the license, as well as the breed, colour and sex of the dog. Dog names occasionally make it into the records too.

The licenses cost 2 shillings per dog and were issued in the same courts as the Petty Sessions. In the first year alone over 350,000 licences were issue and for the rest of the 19th century there were an average of 250,000 licences issued each year.

You can sometimes infer what type of occupation an individual had by their location and the dog they owned. For example, a man living in a rural area who had a breed known as a sheep dog, guard dog or working dog may have been a farmer, whereas a woman living in a city with a lap dog or toy dog may have been married to a well off man and kept the dog as a daily companion.

Irish dog licenses can now be researched on FindMyPast, with new additions being added over time: https://search.findmypast.com/search-world-records/ireland-dog-licence-registers

Credit: Irish Genealogical Research Society.

Emigration Records

No centralised records of emigration exist in Ireland or Britain, but a collection of primary source documents on Irish emigration to North America is available through the Irish Emigration Database online. Commercial websites like Ancestry and FindMyPast have passenger list collections for both departing and arriving travellers.

The Ellis Island Passenger Database has records of people who entered the Unites States between 1892 and 1954 and they usually record the traveller’s place of origin: https://heritage.statueofliberty.org/passenger

Credit: boweryboyshistory.com

The EPIC Irish Emigration Museum in Dublin has fantastic exhibitions about the Irish diaspora: https://epicchq.com/

https://www.irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/Irish-emigration.html

Family History Societies

Family history societies are an invaluable resource when researching ancestors from a particular place and most are helpful to those enquiring about the best strategies to use for a family living in their areas.

The Irish Family History Society (IFHS) is based in Ireland and organises lectures, visits to Archives and Libraries and publishes journals: https://ifhs.ie/

Griffith’s Valuations

Griffith’s Valuation was a land survey conducted between 1847 and 1864 to assess land valuation for taxation purposes and is an essential source for Irish genealogy. Named after the commissioner, Sir Richard Griffith, it was officially known as the Primary Valuation of Ireland.

The names of occupants and landowners, descriptions of the property and land valuations can all be found in the records. There are also accompanying Griffith’s Valuation maps.

FindMyPast have Griffith’s Valuation Records records available on their website and the National Archives of Ireland have them available to view on microfilm. The Land Valuation Office in Dublin also have books which track the changes overtime recorded in revision of the land valuation data.

Ireland to Australia Transportation Database

The National Archives of Ireland holds penal transportation records covering 1788–1868: https://www.nationalarchives.ie/article/penal-transportation-records-ireland-australia-1788-1868-2/

In some records, information about the convicts family are also included, if they also left for Australia as free settlers. This can point to researching in the Free Settlers’ Papers (1828–1852).

After transportation to Australia ended, later transportation was to Bermuda and Gibraltar.

Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead aka Mems Dead

The Journal of the Association for the Preservation of the Memorials of the Dead aka Mems Dead records monumental inscriptions on Irish gravestones.

Latin

Irish Catholic parish records were written in either Latin or English, so it can be handy to recognise some common Latin words/phrases when searching from Irish relatives. Inscriptions on grave stones or memorials are also at times in Latin. Some Latin words you are likely to come across are:

Ablutus/plutus: christening

Compater/commater/levantes: godfather/godmother/godparent

Conjux: husband or wife

Consanguinati: blood related

Coram: in the presence of

Decessit sine prole: died without issue

Denuntiationes: marriage banns

Eodem Die: same day

Genitores: parents

Hic jacet: here lies

Innupta: a woman who died without marrying

Intronisati: marriage

Matrimonium duxit: has married

Mortuus or defunctus: deceased

Natus/oriundus: birth

Parochialis: parish

Solus: single

Testis: witness

Vidua/viduus: Widow/widower

Military Archives

Irish military records can offer a wealth of information about your ancestors and can include battalion diaries, medal rolls, muster rolls, pay lists, pension records, service records and wills. You may even come across a physical or character description depending on the surviving records.

Credit: Pinterest.

It is important to search in the right place depending on the dates your ancestor was in military service:

- 1801-1922 – Irish soldiers were part of the British Army and both Protestant and Catholic men served.

- 1914-1918 – over 200,000 men from Ireland fought in the First World War with the British Army. It has been estimated the 30,000 Irishmen died.

- 1919-1922 – during the Irish War of Independence Irish ex-servicemen from the Great War fought for both sides.

- 1939-1945 – the Republic of Ireland was officially neutral during the Second World War, but about 80,000 Irish people joined the British armed forces and participated in the conflict.

Credit: Wikimedia.

Regimental and Corps Museums or Archives (such as the Inniskillings Museum or Royal Irish Regiment Museum) often hold unique records that aren’t stored elsewhere, so if you know the Regiment it is well worth checking if they hold any information about your relative. The Ogilby Muster is digitising regimental archives to preserve these records and widen access: https://www.theogilbymuster.com/

The National Archives (Great Britain) hold records of the British armed forces: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C543

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) records and maintains the graves and places of commemoration of military service members who died in the two World Wars: https://www.cwgc.org/

Online collections in the Military Archives Ireland include documents from the Republic of Ireland such as the Military Service Pensions Collection (1916 – 1923) and Irish Army Census Collection (1922), whilst the Reading Room offers access to the Civil War Internment Collection (1922-1925): https://www.militaryarchives.ie/en/genealogy

Newspapers

The Irish Newspaper Archive is a subscription based website with papers from as early as 1738: https://www.irishnewsarchive.com/

For Northern Ireland, the British Newspaper Archive has a variety of papers from the region, from the Armagh Guardian to Witness (Belfast): https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/search/results?Region=Northern%20Ireland,%20Northern%20Ireland

Old Irish Naming Conventions

Understanding old Irish naming conventions can be very helpful to Irish family historians, with the Celtic cultural tradition at it’s peak in the 18th and 19th centuries. Whilst not a rule that had to be adhered to, it was a popular custom in families across all social classes in Ireland, but is generally the most prevalent amongst poorer and rural families.

The convention was:

1st son named after the paternal grandfather (his father’s father); 2nd son named after the maternal grandfather (his mother’s father); 3rd son named after his father; 4th son named after his eldest paternal uncle (his father’s eldest brother) and so on.

1st daughter named after the maternal grandmother (her mother’s mother); 2nd daughter named after the paternal grandmother (her father’s mother); 3rd daughter named after her mother; 4th daughter named after her mother’s eldest sister; and so on.

The convention was more strictly followed for sons and if a close family member had recently died sometimes the convention would skip to the next child. The new-born could be named after the recently deceased individual as a mark of respect. Due to the high levels of infant mortality in the past and women dying during childbirth, when a child passed away it was common for names to be reused in a subsequent birth, in order to keep the name alive in the family. When a widower remarried after the customary 12 month mourning period for his spouse, the name of the deceased first wife would often be given to the first daughter of the new wife.

The traditional naming conventions travelled with Irish emigrants to the New World of the Americas with couples honouring their homeland by following the old patterns when naming their children. This can be a helpful clue for names to look out for when tracing the lineages of Irish immigrants back to Ireland or if you are looking for extended family in America or Canada.

Parish Records

The National Library of Ireland has a website dedicated to their collection of Catholic parish register microfilms. The registers contain records of baptisms and marriages from the majority of Catholic parishes in Ireland and Northern Ireland up to 1880: https://registers.nli.ie/

Church of Ireland records can be found at Irish Genealogy: https://churchrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/churchrecords/advanced.jsp

Tithe Applotment Books

Tithe applotment books were compiled between 1823 and 1837 to record the assessments of the tithe tax on agricultural land in Ireland. The tax was equivalent to 1/10 of the produce of agricultural land.

The tax was paid to to the Church of Ireland regardless of denomination, so was resented by the largely Roman Catholic population. From 1831 the ‘Tithe War’ began and many refused to pay the tithes.

The National Archives of Ireland holds the tithe books which can be browsed online for free. They are arranged arranged by Church of Ireland parish for the now Republic of Ireland: http://titheapplotmentbooks.nationalarchives.ie/search/tab/home.jsp

Some tithe records can also be found indexed at FamilySearch or on the Genealogical Society of Ireland website.

Visitations of Ireland

Heraldic Visitations were tours of inspection undertaken by Kings of Arms and are a record of the pedigrees and arms of noble families in England, Wales and Ireland. The visitations were intended to counter the abuse of coats of arms, correct irregularities and ensure that evidence was presented by families to demonstrate their ancestral right to use them. They begun in Ireland in 1568 under the authourity of the provincial Ulster King of Arms.

A distinctive feature of Irish heraldry is the acceptance by the Irish Genealogical Office of ancient clan arms, which belong to descendants of the male lines of Irish clans or septs. In the traditional Gaelic tanistry system for passing on titles and lands, the clan king or chief held office for life and was succeeded by his tanist (heir apparent) who had been elected from another patrilineal branch of the family by eligible male relatives. It was typical for the most ambitious, ruthless and talented son or grandson of a former king to become tanist in a rotation among the most prominent branches of the reigning clan. It could not be claimed through a female line in Ireland as it was an agnatic succession system. Tanistry was eventually replaced by English common law and hereditary succession.

Wills

FindMyPast have an index of Irish wills which cover 1484 – 1858: https://search.findmypast.co.uk/search-world-records/index-of-irish-wills-1484-1858

Good luck… or Go n-éirí an bóthar leat!

Leave a comment